Reinhold Moritzevich Glière | |

|---|---|

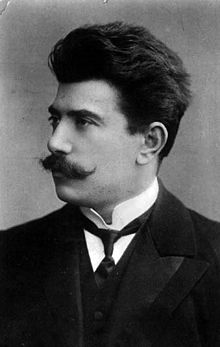

Reinhold Glière as a young man. | |

| Born | Reinhold Ernest Glier 11 January 1875 [O.S. 30 December 1874] |

| Died | 23 June 1956 (aged 81) |

| Other names | Рейнгольд Морицевич Глиэр |

| Citizenship | |

| Alma mater | Moscow Conservatory |

| Occupation | Composer |

Reinhold Moritzevich Glière (Russian: Рейнгольд Морицевич Глиэр, Ukrainian: Ре́йнгольд Мо́ріцевич Гліер / Reingol'd Moritsevich Glier; born Reinhold Ernest Glier, which was later converted for standardization purposes; 11 January 1875 [O.S. 30 December 1874] – 23 June 1956), was a Soviet ukrainian and russian composer, of German and Polish descent.

러시아, 우크라이나, 주변 공화국들의 민속음악 요소들을 통합한 작품으로 유명하다.

벨기에계 러시아인인 글리에르의 아버지는 음악가이자 악기제조업자였다. 그는 아버지를 방문한 사람들이 자신의 초기 작품들을 연주하는 것을 들으면서 자랐고 어린 나이에 키예프에서 음악수업을 받았다. 1900년 모스크바 음악원을 졸업했는데 그곳에서 바이올린과 작곡·음악이론을 배웠다. 모스크바에서 잠시 가르친 뒤, 1905~07년 베를린에서 지휘를 공부했고, 1908년 러시아에서 처음 지휘했으며 그해 교향시 〈사이렌 The Sirens〉이 열렬한 찬사를 받았다. 키예프 음악원에서 가르쳤고 1914년 원장으로 임명되었다.

1920년에 모스크바로 돌아와 모스크바 음악원에서 가르쳤으며 러시아 민속음악 공부에 몰두하여 자료를 모으기 위해 두루 여행했다. 아제르바이잔 민족음악을 연구한 결과 오페라 〈샤 세남 Shah Senam〉(1934 초연)이 나왔으며, 음악극 〈훌사라 Hulsara〉(1936)에는 우즈베크적 요소가 나타난다.

글리에르는 민족음악에 관심이 많았기 때문에 혁명 뒤 소련 음악계에서 높은 자리를 차지했다. 노동자 음악회를 주선했고 모스크바 작곡가 연맹과 소련 작곡가 연맹을 이끌어 정부 훈장을 받았다.

발레 음악인 〈빨간 양귀비 The Red Poppy〉(1927)가 한때 국제적 명성을 얻었지만, 오늘날 글리에르의 음악은 주로 공산국가에서 연주된다. 그밖에 좋은 평가를 받는 작품으로는 발레 음악인 〈청동의 기사 The Bronze Horseman〉(1949)와 교향곡 3번 〈일리야 무로메츠 Il'ya Muromets〉(1909~11) 등이 있다. 소련 작가들에 의해 찬사를 받았지만 〈붉은 군대의 25년〉(1943) 서곡과 〈10월혁명 20주년 축전 서곡〉(1937) 같은 작품은 깊이와 창의성이 없다는 이유로 비판을 받았다. 그럼에도 불구하고 그가 소련의 젊은 작곡가들에게 끼친 영향은 크다. 제자 가운데는 세르게이 프로코피예프, 니콜라이 먀스코프스키, 아람 하차투리안이 있다. [다음백과]

Glière was born in Kiev. He was the second son of the wind instrument maker Ernst Moritz Glier (1834–1896) from Saxony (Klingenthal), who emigrated to the Russian Empire and married Józefa (Josephine) Korczak (1849–1935), the daughter of his master, from Warsaw. His original name, as given in his baptism certificate, was Reinhold Ernest Glier.[1] About 1900 he changed the spelling and pronunciation of his surname to Glière, which gave rise to the legend, stated by Leonid Sabaneyev for the first time (1927), of his French or Belgian descent.[2]

He entered the Kiev school of music in 1891, where he was taught violin by Otakar Ševčík, among others. In 1894 Glière entered the Moscow Conservatory where he studied with Sergei Taneyev (counterpoint), Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov (composition), Jan Hřímalý (violin; he dedicated his Octet for Strings, Op. 5, to Hřímalý), Anton Arensky and Georgi Conus (both harmony). He graduated in 1900, having composed a one-act opera Earth and Heaven (after Lord Byron) and received a gold medal in composition.[1] In the following year Glière accepted a teaching post at the Moscow Gnesin School of Music. Taneyev found two private pupils for him in 1902: Nikolai Myaskovsky and the eleven-year-old Sergei Prokofiev, whom Glière taught on Prokofiev's parental estate Sontsovka.[3] Glière studied conducting with Oskar Fried in Berlin from 1905 to 1908. one of his co-students was Serge Koussevitzky, who conducted the premiere of Glière's Symphony No. 2, Op. 25, on 23 January 1908 in Berlin. Back in Moscow, Glière returned again to the Gnesin School. In the following years Glière composed the symphonic poem Sireny, Op. 33 (1908), the programme symphony Ilya Muromets, Op. 42 (1911) and the ballet-pantomime Chrizis, Op. 65 (1912). In 1913 he gained an appointment to the school of music in Kiev, which was raised to the status of conservatory shortly after, as Kiev Conservatory. A year later he was appointed director. In Kiev he taught among others Levko (Lev) Revoutski, Borys Lyatoshynsky and Vladimir Dukelsky (who became well known in the West as Vernon Duke).

In 1920 Glière moved to the Moscow Conservatory where he (intermittently) taught until 1941. Boris Alexandrov, Aram Khachaturian, Alexander Davidenko, Lev Knipper and Alexander Mosolov were some of his pupils from the Moscow era. For some years he held positions in the organization Proletkul't and worked with the People's Commissariat for Education. The theatre was in the centre of his work now. In 1923 Glière was invited by the Azerbaijan People's Commissariat of Education to come to Baku and compose the prototype of an Azerbaijani national opera. The result of his ethnographical research was the opera Shakh-Senem, now considered the cornerstone of the Soviet-Azerbaijan national opera tradition. Here the musical legacy of the Russian classics from Glinka to Scriabin is combined with folk song material and some symphonic orientalisms. In 1927, inspired by the ballerina Yekaterina Vasilyevna Geltzer (1876–1962), he wrote the music for the ballet Krasny mak (The Red Poppy), later revised, to avoid the connotation of opium, as Krasny tsvetok (The Red Flower, 1955). The Red Poppy was praised "as the first Soviet ballet on a revolutionary subject". Perhaps this is his most famous work in Russia as well as abroad. one number from the score, his arrangement of a Russian folk chastushka song Yablochko ("little apple") consists of an introduction, a basso statement of the theme, and a series of increasingly frenetic variations ending with a powerful orchestral climax. It is identified in the ballet score by its almost equally well-known name, the Russian Sailor's Dance. It is probably his best-known single piece, and is still heard at symphony concerts around the world, frequently as an encore. The ballet-pantomime Chrizis was revised just after The Red Poppy, in the late 1920s, followed by the popular ballet Comedians after Lope de Vega (1931, later re-written and renamed The Daughter from Castile).

After 1917 Glière never visited Western Europe, as many other Russian composers did. He gave concerts in Siberia and other remote areas of Russia instead. He was working in Uzbekistan as a "musical development helper" at the end of the 1930s. From this time emerged the "drama with music" Gyulsara and the opera Leyli va Medzhnun, both composed with the Uzbek Talib Sadykov (1907–1957). From 1938 to 1948 Glière was Chairman of the Organization Committee of the Soviet Composers Association. Before the revolution Glière had already been honoured three times with the Glinka prize. During his last few years he was very often awarded: Azerbaijan (1934), the Russian Soviet Republic (1936), Uzbekistan (1937) and the USSR (1938) appointed him Artist of the People. The title "Doctor of Art Sciences" was awarded to him in 1941. He won first degree Stalin Prizes: in 1946 (Concerto for Voice and Orchestra), 1948 (Fourth String Quartet), and 1950 (The Bronze Horseman).

As Taneyev's pupil and an 'associated' member of the circle around the Petersburg publisher Mitrofan Belyayev, it appeared Glière was destined to be a chamber musician. In 1902 Arensky wrote about the Sextet, Op. 1, one recognizes Taneyev easily as a model and this does praise Glière". Unlike Taneyev, Glière felt more attracted to the national Russian tradition as he was taught by Rimsky-Korsakov's pupil Ippolitov-Ivanov. Alexander Glazunov even certified an "obtrusively Russian style" to Glière's 1st Symphony. The 3rd Symphony Ilya Muromets was a synthesis between national Russian tradition and impressionistic refinement. The premiere was in Moscow in 1912, and it resulted in the award of the Glinka Prize. The symphony depicts in four tableaux the adventures and death of the Russian hero Ilya Muromets. This work was widely performed, in Russia and abroad, and earned him worldwide renown. It became an item in the extensive repertoire of Leopold Stokowski, who made, with Glière's approval, an abridged version, shortened to around the half the length of the original. Today's cult status of Ilya Muromets is based not least on the pure dimensions of the original 80-minute work, but Ilya Muromets demonstrates the high level of Glière's artistry. The work has a comparatively modern tonal language, massive Wagnerian instrumentation and long lyrical lines.

Notwithstanding his political engagement after the October revolution Glière kept out of the ideological ditch war between the Association for Contemporary Music (ASM) and the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM) during the late 1920s. Glière concentrated primarily on composing monumental operas, ballets, and cantatas. His symphonic idiom, which combined broad Slavonic epics with cantabile lyricism, is governed by rich, colourful harmony, bright and well-balanced orchestral colours and perfect traditional forms. Obviously this secured his acceptance by Tsarist and Soviet authorities, at the same time creating resentment from many composers who suffered intensely under the Soviet regime. As the last genuine representative of the pre-revolutionary national Russian school, i.e. a 'living classic', Glière was immune to the standard reproach of "formalism" (mostly equivalent to "modernity" or "bourgeois decadence"). Thus the infamous events of 1936 and 1948 passed Glière by.

Gliere wrote concerti for harp (Op. 74, 1938), coloratura soprano (Op. 82, 1943), cello (Op. 87, 1946, dedicated to Sviatoslav Knushevitsky), horn (Op. 91, 1951, dedicated to Valery Polekh), and violin (Op. 100, 1956, unfinished, completed by Boris Lyatoshinsky). Nearly unexplored are Glière's educational compositions, his chamber works, piano pieces and songs from his time at the Moscow Gnesin School of Music.

He died in Moscow on 23 June 1956.

'♣ 음악 감상실 ♣ > [1860년 ~1880년]' 카테고리의 다른 글

| [러시아계 스위스]Paul Juon (0) | 2020.07.24 |

|---|---|

| [영국 - 기관지 천식으로 요절한 음악가]William Hurlstone (0) | 2020.05.25 |

| [프랑스] Louis Thirion (0) | 2019.12.07 |

| [프랑스] Léon Boëllmann (0) | 2019.11.26 |

| [오스트리아]Ludwig Thuile (0) | 2019.11.04 |