Hieronymus Bosch (/ /; Dutch: [ɦijeˈɾoːnimʏs ˈbɔs]; born Jheronimus van Aken [jeˈɾoːnimʏs vɑn ˈaːkə(n)];[1] c. 1450 – 9 August 1516) was an Early Netherlandish painter. His work is known for its use of fantastic imagery to illustrate moral and religious concepts and narratives.[2]

Hieronymus Bosch was born Jheronimus (or Joen,[3] respectively the Latin and Middle Dutch form of the name "Jerome") van Aken (meaning "from Aachen"). He signed a number of his paintings as Jheronimus Bosch (pronounced Jeronimus Bos in Middle Dutch).[4] The name derives from his birthplace, 's-Hertogenbosch, which is commonly called "Den Bosch".

Little is known of Bosch’s life or training. He left behind no letters or diaries, and

what has been identified has been taken from brief references to him in the municipal records of 's-Hertogenbosch, and in the account books of the local order of the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady. Nothing is known of his personality or his thoughts on the meaning of his art. Bosch’s date of birth has not been determined with certainty. It is estimated at c. 1450 on the basis of a hand drawn portrait (which may be a self-portrait) made shortly before his death in 1516. The drawing shows the artist at an advanced age, probably in his late sixties.[5]

Bosch was born and lived all his life in and near ‘s-Hertogenbosch, a city in the Duchy of Brabant. His grandfather, Jan van Aken (died 1454), was a painter and is first mentioned in the records in 1430. It is known that Jan had five sons, four of whom were also painters. Bosch’s father, Anthonius van Aken (died c. 1478), acted as artistic adviser to the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady.[6] It is generally assumed that either Bosch’s father or one of his uncles taught the artist to paint, but none of their works survive.[7] Bosch first appears in the municipal record on 5 April 1474, when he is named along with two brothers and a sister's-Hertogenbosch was a flourishing city in fifteenth century Brabant, in the south of the present-day Netherlands, at the time part of the Burgundian Netherlands, and during his lifetime passing through marriage to the Habsburgs. In 1463, 4,000 houses in the town were destroyed by a catastrophic fire, which the then (approximately) 13-year-old Bosch presumably witnessed. He became a popular painter in his lifetime and often received commissions from abroad. In 1488 he joined the highly respected Brotherhood of Our Lady, an arch-conservative religious group of some 40 influential citizens of 's-Hertogenbosch, and 7,000 'outer-members' from around Europe.

Sometime between 1479 and 1481, Bosch married Aleyt Goyaerts van den Meerveen, who was a few years his senior. The couple moved to the nearby town of Oirschot, where his wife had inherited a house and land from her wealthy family.[8]

An entry in the accounts of the Brotherhood of Our Lady records Bosch’s death in 1516. A funeral mass served in his memory was held in the church of Saint John on 9 August of that year.[9]

Art

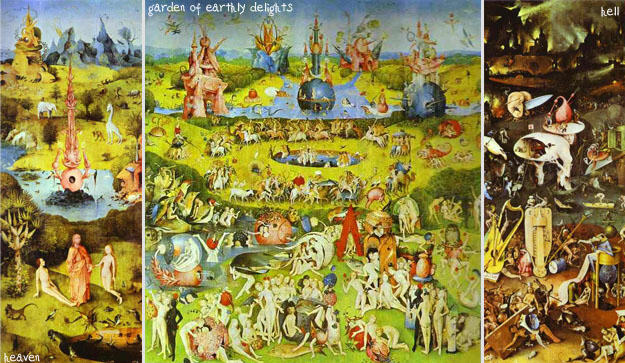

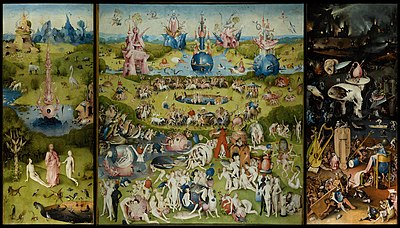

Bosch produced several triptychs. Among his most famous is The Garden of Earthly Delights. This painting, for which the original title has not survived, depicts paradise with Adam and Eve and many wondrous animals on the left panel, the earthly delights with numerous nude figures and tremendous fruit and birds on the middle panel, and hell with depictions of fantastic punishments of the various types of sinners on the right panel. When the exterior panels are closed the viewer can see, painted in grisaille, God creating the Earth. These paintings—especially the Hell panel—are painted in a comparatively sketchy manner which contrasts with the traditional Flemish style of paintings, where the smooth surface—achieved by the application of multiple transparent glazes—conceals the brushwork. In this painting, and more powerfully in works such as his Temptation of St. Anthony, Bosch draws with his brush. Bosch also produced some of the first autonomous sketches in Northern Europe.

Bosch's paintings with their rough surfaces, so called impasto painting, differed from the tradition of the great Netherlandish painters of the end of the 15th, and beginning of the 16th centuries, who wished to hide the work done and so suggest their paintings as more nearly divine creations.[10]

Bosch never dated his paintings. But—unusual for the time—he seems to have signed several of them, although some signatures purporting to be his are certainly not. Fewer than 25 paintings remain today that can be attributed to him. In the late sixteenth-century, Philip II of Spain acquired many of Bosch's paintings, including some probably commissioned and collected by Spaniards active in Bosch's hometown; as a result, the Prado Museum in Madrid now owns The Adoration of the Magi, The Garden of Earthly Delights, the tabletop painting of The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things, the The Haywain Triptych and The Stone Operation.

Interpretations

In the twentieth century, when changing artistic tastes made artists like Bosch more palatable to the European imagination, it was sometimes argued that Bosch’s art was inspired by heretical points of view (e.g., the ideas of the Cathars and putative Adamites) as well as by obscure hermetic practices. Again, since Erasmus had been educated at one of the houses of the Brethren of the Common Life in 's-Hertogenbosch, and the town was religiously progressive, some writers have found it unsurprising that strong parallels exist between the caustic writing of Erasmus and the often bold painting of Bosch. "Although the Brethren remained loyal to the Pope, they still saw it as their duty to denounce the abuses and scandalous behaviour of many priests: the corruption which both Erasmus and Bosch satirised in their work".[11]

Others, following a strain of Bosch-interpretation datable already to the sixteenth-century, continued to think his work was created merely to titillate and amuse, much like the "grotteschi" of the Italian Renaissance. While the art of the older masters was based in the physical world of everyday experience, Bosch confronts his viewer with, in the words of the art historian Walter Gibson, "a world of dreams [and] nightmares in which forms seem to flicker and change before our eyes". In one of the first known accounts of Bosch’s paintings, in 1560 the Spaniard Felipe de Guevara wrote that Bosch was regarded merely as "the inventor of monsters and chimeras". In the early seventeenth century, the Dutch art historian Karel van Mander described Bosch’s work as comprising "wondrous and strange fantasies"; however, he concluded that the paintings are "often less pleasant than gruesome to look at".[12]

In recent decades, scholars[who?] have come to view Bosch's vision as less fantastic, and accepted that his art reflects the orthodox religious belief systems of his age.[citation needed] His depictions of sinful humanity and his conceptions of Heaven and Hell are now seen as consistent with those of late medieval didactic literature and sermons. Most writers attach a more profound significance to his paintings than had previously been supposed, and attempt to interpret it in terms of a late medieval morality. It is generally accepted that Bosch’s art was created to teach specific moral and spiritual truths in the manner of other Northern Renaissance figures, such as the poet Robert Henryson, and that the images rendered have precise and premeditated significance. According to Dirk Bax, Bosch's paintings often represent visual translations of verbal metaphors and puns drawn from both biblical and folkloric sources.[13] However, the conflict of interpretations that his works still elicit raises profound questions about the nature of "ambiguity" in art of his period.

In recent years, art historians have added a further dimension again to the subject of ambiguity in Bosch’s work. They emphasized his ironic tendencies, which are fairly obvious, for example, in the The Garden of Earthly Delights, both in the central panel (delights),[14] and the right panel (hell).[15] By adding irony to his morality arenas, Bosch offers the option of detachment, both from the real world and from the painted fantasy world. By doing so he could gain acceptance among both conservative and progressive viewers. Perhaps it was just this ambiguity that enabled the survival of a considerable part of this provocative work through five centuries of religious and political upheaval.

A recent study[16] on Bosch's paintings alleges that they actually conceal a strong nationalist consciousness, censuring the foreign imperial government of the Burgundian Netherlands, especially Maximilian Habsburg. By systematically superimposing images and concepts, the study asserts that Bosch also made his expiatory self-punishment, for he was accepting well-paid commissions from the Habsburgs and their deputies, and therefore betraying the memory of Charles the Bold.[17]

Debates on attribution

The exact number of Bosch's surviving works has been a subject of considerable debate. He signed only seven of his paintings, and there is uncertainty whether all the paintings once ascribed to him were actually from his hand. It is known that from the early sixteenth century onwards numerous copies and variations of his paintings began to circulate. In addition, his style was highly influential, and was widely imitated by his numerous followers.[18]

Over the years, scholars have attributed to him fewer and fewer of the works once thought to be his, and today only 25 are definitively attributed to him.

Works